Several parts of Canada were affected by extreme dry conditions in 2023, from Nova Scotia to Northwest Territories, including many areas of Quebec, Alberta, and British Columbia. This resulted in the worst wildfire season in the history of the country. Yukoners were relatively fortunate during most of the summer, but Mayo and Old Crow had to be evacuated because of the proximity of the flames. This blog post emphasizes the impact of climate change on floods, but 2023 should also be remembered for revealing our collective vulnerability to a wide range of weather extremes influenced by climate change.

***

For most watersheds of the Yukon, the 2023 snowpack did not contain as much water as it did in recent years. Nonetheless, the snow water equivalent was above average in several areas, including near Carmacks, Beaver Creek, Dawson City, and Old Crow as well as along the Dempster Highway. In addition, river ice conditions represented a source of concern near Dawson and Rock Creek, a consequence of an intense (or dynamic) freeze-up in the previous (2022) fall.

Southern Lakes and Kwänlin (Whitehorse and surroundings):

After breaking hydrological records in 2021 (highest water level in more than 100 years) and 2022 (latest natural peak on record since 1920), Southern Lakes behaved somewhat normally in 2023, which was welcomed by locals. However, hydrological extremes occurred at a different scale. On July 23, Kwänlin was soaked by more than 20 mm of rain in a few hours, enough to overwhelm most urban drainage systems. Streets became creeks, properties were flooded, and erosion occurred at several, generally unpaved locations. Reports of damage provide an opportunity to target improvements to the sizing and design of runoff drainage and storage infrastructure. At a local scale, especially in an urban setting, severe rain events can produce much higher runoff rates than snowmelt alone.

Carmacks area:

Both the Deisleen Kwàan (Teslin River) and Tàgé Cho Gé (Yukon River) remained within their normal range in 2023. At a smaller scale (in terms of watershed area), the discharge of the Tsâwnjik Chu (Nordenskiold River) almost reached 200 cubic meters per second (m3/s) on May 19, a condition that only occurs once every 20 years, on average. It was the highest flow since 2009; high enough for the Emergency Measure Organization to release a public flood watch. It is important to note, however, that in most years, the highest water levels in the Tsâwnjik Chu are associated with river ice formation (in November and December) or river ice breakup (in late April or early-May).

Nêtʼił Tué’ (Liard River), Ts’ekínyäk Chú (Pelly River), and Nä`chòo ndek (Stewart River) watersheds

Flow conditions remained close to average in all three rivers during the snowmelt period, and this was followed by a relatively dry and warm summer (with very high air temperatures at the beginning of July). Rain events brought flows back up to normal by the end of September.

ʼAt’aayaat Chù’ (Southern Tutchone) or Tadzan ndek (Hän) (White River):

For a third time since 2020, a glacial lake released from the terminus of Russell Glacier in Alaska, located in the headwaters of the ʼAt’aayaat Chù’ or Tadzan ndek (White River). This caused relatively high flows at the Water Survey of Canada station 09CB001 on August 16-17, but the event was not as dramatic as it was in 2020 when a sudden release of the same glacial lake produced the peak flow of the year. This phenomenon will be explained in more detail in an ArcticNet Chapter to be published in 2024.

Central Yukon and Dawson area:

The formation of the ice cover in the Chu kon’ dëk (Yukon River) downstream of Dawson was unusually dynamic in November 2022. This represented a concern for river ice breakup in the spring of 2023. Frequent snow events in April prevented the ice cover from weakening as breakup was approaching, and this was also not ideal from a flood risk perspective. Air temperatures rose rather suddenly on May 6, and this was enough to send a significant amount of snowmelt runoff into the streams feeding into the Chu kon’ dëk. Recent analyses suggest that the strong ice cover upstream of Dawson contributed to delaying breakup and an ice run from the Nä`chòo ndek (Stewart River) caused breakup through Dawson 24 hours later. The water level rose by 1.5 m during the event along the dike and this did not represent any concern from a safety perspective. The ice run was relatively short (in both time and length) because most of the broken ice cover had been stored in the multiple secondary channels of the Chu kon’ dëk upstream of Dawson.

Sadly, the historic village of Forty Mile was severely impacted by an ice jam a few days later, with water levels reaching the roof of buildings (see picture taken by the Yukon Government on May 11). This event suggests that a major ice jam in the Chu kon’ dëk at Dawson remains possible, even though the last significant event in the community occurred more than 40 years ago (in 1979). Moreover, it appears that the dike at Dawson could be challenged by an ice jam which intensity would compare to that of the 2023 Forty Mile ice jam.

Historic village of Forty Mile located 80 km downstream of Dawson on May 12, 2023. Photo provided by the Government of Yukon as part of a project on river ice breakup forecasting.

The formation of the ice cover in the Tr’ondëk (Klondike River) had also been dynamic during the fall of 2022, with minor overbank flooding at some locations at the end of November. In May 2023, a significant amount of snowmelt water reached the valley bottom well before the ice cover was ready to break. This resulted in an uncommon combination of several short ice jams resisting a flow above 400 m3/s (a previous blog post explains the breakup sequence). Ice jams at Henderson Corner, Rock Creek, and the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Farm caused significant damage to properties along the river. Government properties, including the Klondike River campground, the Klondike Highway, and the airport were affected by high water levels to different degrees (see pictures below). Backwater through drainage culverts was reported at several locations; an indication that adaptation of this infrastructure is required.

Top: Flooded Klondike River campground (May 10, 2023). Middle: Temporary dike built on the Klondike Highway at Henderson Corner (May 11, 2023). Bottom: Ditch filled up with water from the Klondike River along the Klondike Highway at the Dawson airport (May 10, 2023). All photos by YukonU Research Centre.

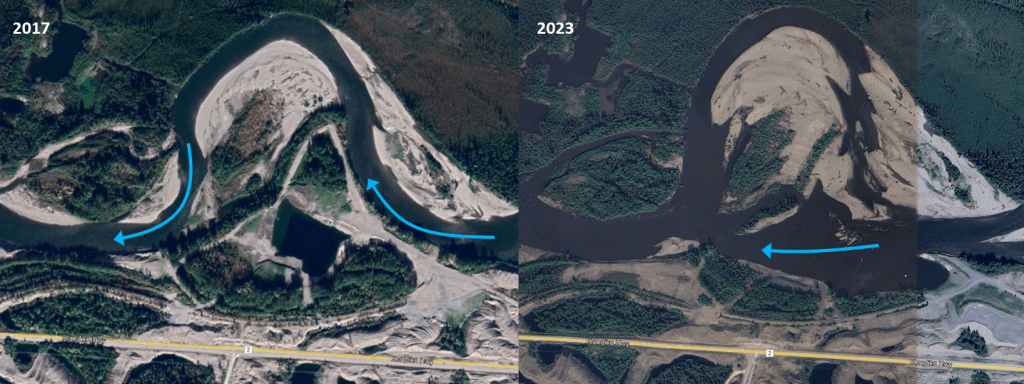

Residents and businesses in the Klondike River valley were not out of trouble yet. Just like in 2013, ice jam floods were followed by an extreme high flow event a few weeks later. A rain event on a residual snowpack made the discharge of the Tr’ondëk rise to almost 1000 m3/s. Distinct areas were flooded along the river and additional water and erosion damage occurred. This rain event also affected other watersheds in central Yukon, including Clear Creek, where overflow impacted the Klondike Highway. Our research team was fortunate to retrieve all the water level loggers from the Tr’ondëk later during the summer. In the end, only one trail camera was lost; it had been attached to a tree on a bank that was washed out, which resulted in a meander cut (see image below: the Tr’ondëk is now 600 m shorter). The retrieved data was used to better understand the breakup sequence in the Tr’ondëk, which is essential to support river ice breakup forecasting, land development planning, and flood risk reduction strategizing.

Satellite images (Google Earth) from 2017 and 2023 showing the Tr’ondëk meander cut near Bear Creek subdivision following the 2023 dynamic river ice breakup event and subsequent record high flow. (Note that the beach project at that location had not been initiated back yet in 2017.)

Aalseix̱’ (Tlingit) or Àłsêxh (Southern Tutchone) (Alsek River):

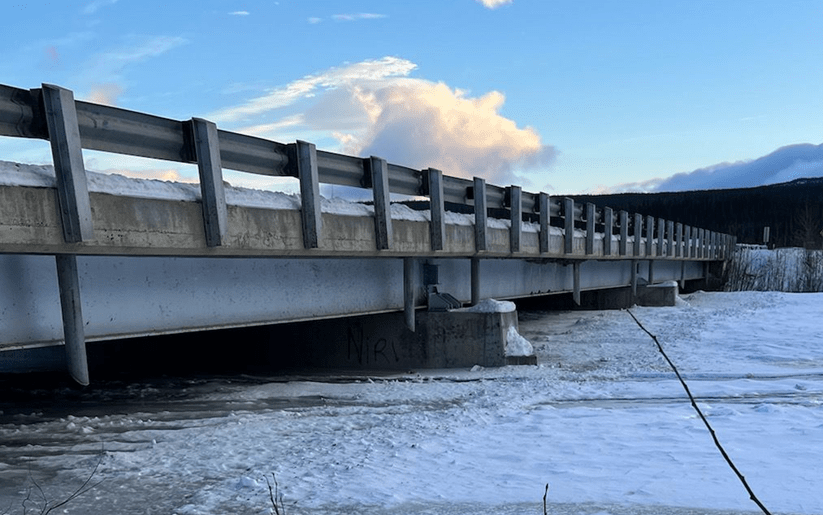

Water levels in the Dezadeash River rose by 2 m during the months of November and December 2022. By the end of the calendar year, the ice surface was almost impacting one of the two Haines Highway bridges (see picture below). This freeze-up process was the direct consequence of record high flows in several rivers of southwestern Yukon during the month of October 2022 (see blog post from the previous hydrological year). As expected, water levels gradually declined during the winter months and a thermal type of breakup occurred between April 9 and May 9.

Dezadeash River bridge near near Haines Junction in mid-December 2022. The ice level eventually reached the vertical pipes (drainage spouts). Photo provided by the Government of Yukon.

Further downstream, for an eighth year in a row, the discharge of the Aalseix̱’ (or Àłsêxh, Alsek River) was well above historical average for most of the summer period, setting new daily records, especially at the end of August. This hydrological behaviour is mostly attributed to the additional glacier contribution from the Tänshı̨̄ (Kaskawulsh Glacier, Southern Tutchone) that used to feed Łù’àn Män (Kluane Lake) through the A’ay Chù (Slims River), a direct and severe result of climate change.

Ch’oodeenjìk (Porcupine River):

The combination of a thick snowpack and a quick rise in air temperatures in May caused a dynamic breakup in the Ch’oodeenjìk (Porcupine River). The river broke, mobilized, and cleared its ice cover over hundreds of kilometers in less than 3 days. Even in the absence of an ice jam, minor flooding occurred near the airport on May 13, a scenario that compares with the dynamic breakup of spring 2020. In recent years, a majority of breakup events in the Ch’oodeenjìk occurred rather suddenly in the presence of a relatively intact ice cover downstream of Old Crow, which aligns with what Ric Janowicz, former flood forecaster and senior hydrologist for the Government of Yukon, had presented in his 2017 CRIPE paper. Breakup events occurring in the Ch’oodeenjìk when the flow is about 4000 m3/s at Old Crow seem relatively common, and each event has the potential to generate a significant flood in the community if the ice run stalls within 40 km downstream of Old Crow.

On May 15, the snowmelt-driven discharge of the Ch’oodeenjìk at Old Crow almost reached 6000 m3/s, a 10-year event that generated slightly higher water levels than the May 13 breakup ice run. Both events are reminders of the high flood probability in Old Crow.

Teetł’it Gwinjik (Peel River in Gwich’in):

A very intense river ice breakup scenario also took place on a long stretch of the Teetł’it Gwinjik (Peel River), causing major flooding in Fort McPherson, Northwest Territories. The ice run even damaged the Water Survey of Canada station 10MC002 located upstream of the community, therefore impacting breakup monitoring and ice-jam flood documentation (the available data shows a river stage rise in the order of 8 m during breakup). It was the third year in a row that a major ice jam flood affected a community in our neighbour territory.

2024 perspective:

It is too early to project how the hydrological year of November 2023 to October 2024 will look. However, three facts are worth mentioning:

- The La Niña weather pattern (cold and snowy conditions in most parts of Yukon) has ended, and a El Niño cycle fed by climate change has started (warmer and dryer conditions are expected in some parts of Yukon). This change in global ocean and atmospheric circulation will have an impact on hydrological conditions next spring and summer, but outcomes are unpredictable.

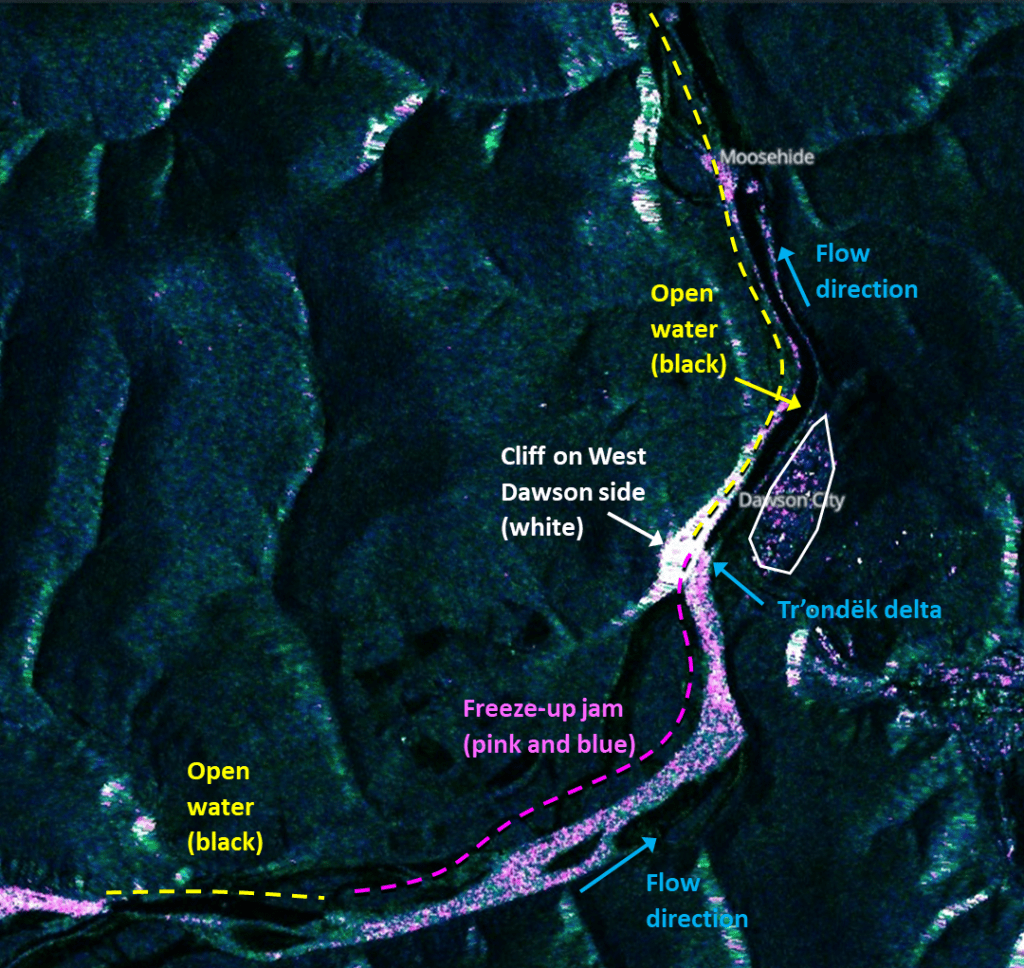

- The Tágà Shäw (Yukon River) at Dawson only formed a partial ice cover, just like in 2013 and from 2016 to 2018 (see radar satellite image below). Some people may believe that warmer weather in the fall caused this, but this is not entirely accurate. In fact, this condition resulted from the formation of a freeze-up jam upstream of the Tr’ondëk delta on November 21 at about 2 am. In this paper, the author explains freeze-up patterns in the Tágà Shäw. The proposed hypothesis is that a freeze-up jam forming immediately upstream of Dawson is the result of 1. relatively low flow conditions (indirectly caused by a warmer and dryer month of November) and 2. a wider Tr’ondëk delta, recently fed with a new layer of river stones dragged by the very high flow of May 2023 (a similar high flow event occurred in the spring of 2013). This situation is highly problematic for the preparation of an ice bridge. Nevertheless, it may represent good news for spring breakup.

- The Tr’ondëk froze at a very high level at the Klondike Highway bridge just out of Dawson. This represents a concern because the last time a comparably intense freeze-up took place (in the fall of 2002), a breakup ice jam flooded what is now the C-4 subdivision in the following spring (2003).

Sentinel 1 satellite product showing the location of the freeze-up jam and open water areas in the Tágà Shäw at Dawson on November 24, 2023. The open water area extends well downstream of Moosehide.