The spring of 2023 has not been gentle on properties and infrastructure located in the Tr’ondëk (Klondike River) floodplain. Severe ice jams caused significant damage between May 7 and May 14. This was followed by a record (since 1970) high flow late on May 24.

Factors that led to severe ice jamming at Henderson Corner, Rock Creek, and Tr’ondëk Farm

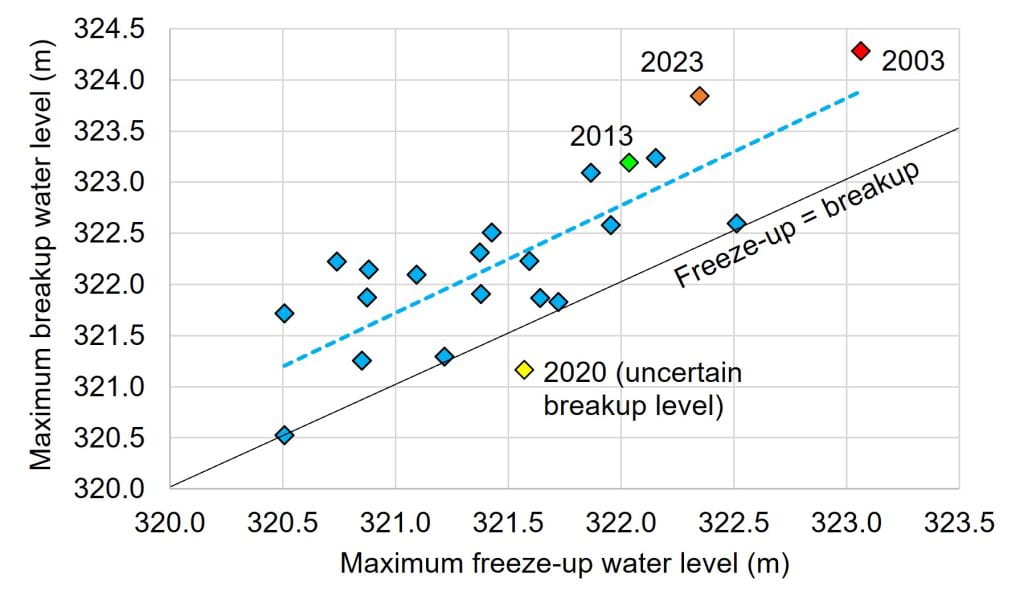

During the fall of 2022, the ice cover in the Tr’ondëk formed at an unusually high discharge resulting from a wet October. This caused the ice cover to be very thick and strong right at the beginning of the cold season. The cold snap of December also contributed to a fast thickening of the ice, making it even stronger. The graph below shows a correlation between the maximum water level at freeze-up and the maximum breakup water level during the following spring at the Klondike Highway bridge (data from 2000 to 2023). This means that a high flow prior to freeze-up increases the probability of ice jam floods in the spring.

A lot of snow fell in the watershed during the winter of 2022-23. Snowpack anomalies of about 135% (35% more than normal) were reported by the Yukon Government in April 2023. Additionally, more various snowfalls occurred in April and air temperatures remained cold. The consequences of these weather conditions were:

- A significant volume of water would flow through the Tr’ondëk system during the snowmelt period.

- The ice cover remained intact and resistant to the increasing flow at the onset of snowmelt.

The river ice breakup sequence was not triggered by a significant rain event or an intense heat wave; air temperatures simply returned to normal with a single warmer-than-normal day (May 6). This was enough for snowmelt runoff to mobilize the ice cover at several locations. In a matter of days, large ice jams had formed in the lower Tr’ondëk, causing flow instabilities that made the system quite unpredictable (ice conditions were unstable over several days).

Chronology and intensity of ice jam floods near Rock Creek

Rock Creek was flooded by an ice jam during the afternoon of May 7. On the morning of May 10, there was still four ice jams between Rock Creek and the Dempster Highway bridge (21 km, 26 km, 28 km, and 41 km upstream of Dawson) and they were all located in multichannel reaches. It was very unlikely that these jams would release without causing further damage to properties. The following figure presents an attempt to explain what happened in the Tr’ondëk over two days. Henderson Corner (Km 26) was badly affected by the release of the Km 28 jam on May 10 at 4 pm. Then, the release of the Km 41 jam on May 12 caused the release of the Henderson Corner and Rock Creek jams, and another major ice jam formed below the airport, affecting the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Farm (16 km above Dawson). This jam stayed in place for 24 hours.

Depending on the exact location, ice jam flood levels during the breakup period of 2023 in the Tr’ondëk were associated with a return period of about 10 to 50 years (with an annual probability of 10% to 2%, respectively). What is remarkable is that the most resistant ice jams stayed in place when the discharge in the Tr’ondëk was as high as 450 m3/s (the average peak flow of the year). A large portion of this water was flowing in secondary channels, on properties, and even across the highway and up culverts.

Conditions leading to the extreme flood of May 24, 2023

Snowmelt runoff rates were just starting to decline in Central Yukon when a rain-on-snow event occurred between May 21 and 24. Rain accumulations of 30 to 40 mm were recorded near Mayo, Stewart Crossing, and Clear Creek (Mike Smith, Yukon Government, pers. com.).

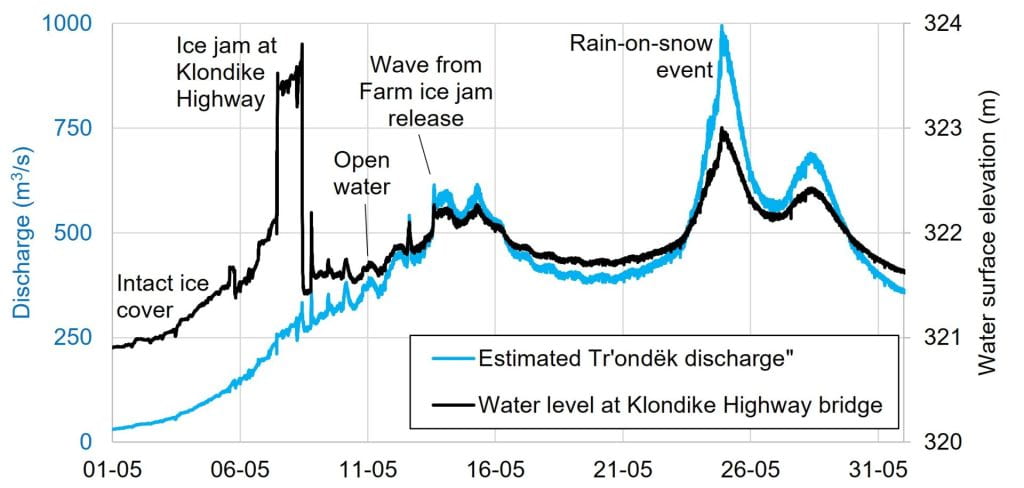

Based on an analysis of peak flows for the period of 1970-2022, a discharge of about 970 m3/s was associated with a return period of 200 years (a flow equal or higher than that would only occur once every 200 years, on average). The peak flow of May 26, 2023, reached 1000 m3/s, beating the previous records from 1972 and 2013 (840 m3/s). The graph below presents the estimated flow and water level in May 2023 at the Water Survey of Canada station 09EA003 on the Tr’ondëk at the Klondike Highway bridge.

Despite its impressive peak flow, the volume of water associated with that 5-day (May 22-26) hydrological event corresponds to a net rain runoff of only 10 to 20 mm. This indicates that, overall, the rainstorm did not affect the entire Tr’ondëk watershed and/or that the top ground layer might have absorbed part of the rain (i.e., in snow-free areas).

Climate change impacts on floods in the Tr’ondëk: Take-home message

The graph below suggests that trends in maximum water levels associated with river ice breakup, open water conditions, and river ice formation are increasing in the Tr’ondëk after mid-1990s. These trends, however, are not statistically significant, and, in the case of ice processes, only apply to a single location. Nonetheless, climate change is known to generate high annual precipitation and more frequent extreme events, including rainstorms and heat waves. The Tr’ondëk, with its high gradient and relatively responsive watershed, is vulnerable to these conditions.

The flooding events of May 2023 represent an opportunity to learn:

- Even mild winters can be followed by extreme ice jam floods in the Tr’ondëk because the thickness of the ice cover is not controlled by air temperatures alone. In fact, rain-on-snow events during early- and late-winter have the potential to exacerbate the intensity of ice jams.

- Some ice jams may stay in place under very high flow conditions. This challenges the empirical concepts of a breakup discharge threshold or the physical concept of increasing hydrodynamic force applied on an ice cover to set it in motion. Both concepts may only apply to single-channel river reaches with a small floodplain. It seems that ice jams will remain a dominant flooding process at most locations along the lower Tr’ondëk in decades to come.

- A flow of 1000 m3/s in the Tr’ondëk is no longer a 250-year event, it is now a 50-year event, and its frequency will likely continue to increase. Future rainstorms during the spring (when the ground is frozen or saturated) will cause flows higher than 1000 m3/s in the Tr’ondëk, with consequent high water levels, erosion, and a reconfiguration of the channel (e.g., the channel width may increase). It has recently been observed more than once that Nature can produce more than 40 mm of rain in 48 hours over large areas in Central Yukon.

From a public safety perspective, considering the current number of vulnerable properties and infrastructure in or close to the Tr’ondëk channel, foreseeing and forecasting floods in that river system is of increasing importance. Flood adaptation, development planning, and infrastructure design will also need to take the current and future hydrological regime of the Tr’ondëk into account. This applies to the communities of Rock Creek and Henderson Corner as well as to the Klondike Highway and to the City of Dawson.

Research on flooding processes at the YukonU Research Centre, Climate Change Research Group

The Hydrology team is working on highwater issues along the Tr’ondëk in the context of two distinct research projects:

- Improving the resilience of the transportation infrastructure (supported by Transport Canada, in partnership with the Department of Highways and Public Works), including predicting and mitigating erosion encroachment and road washouts.

- Developing ice jam flood forecasting capacity (with the Water Resources Branch of the Yukon Government Department of Environment)