Each time a new climate record is broken, climate researchers are left wondering “was this because of our uncontrolled emission of greenhouse gasses?” We rarely know for sure. While a single extreme may be consistent with what was anticipated, specific “attribution” studies are required to determine the contribution of anthropogenic forcing to a given extreme event.

Without digging deeper on identifying the exact role of human activity, this blog focuses on documenting several events in the 2022 hydrological year that caught the attention of water enthusiasts. In short – the sheer number of record events itself is a record to note. Below, we discuss hydrologic responses to weather conditions throughout Yukon with the hope that future study by other climatologists can help determine how common these weather events may become in the future.

Southern Lakes:

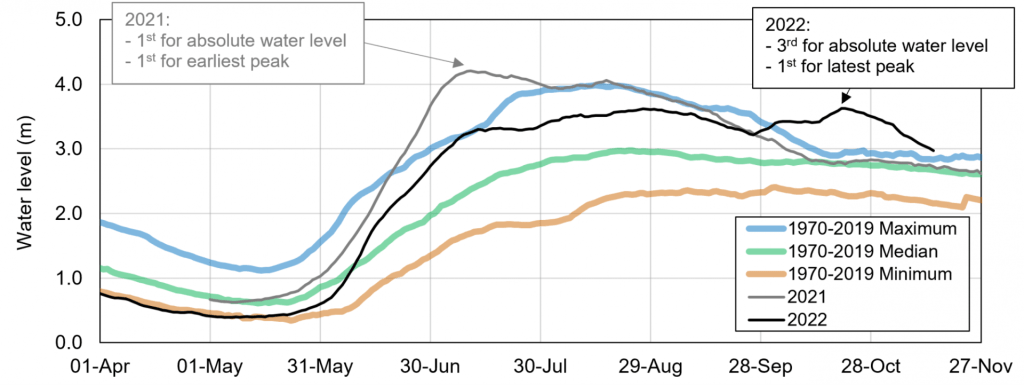

Most Yukoners will remember the record flood of 2021, with Marsh Lake, Tagish Lake, and Bennett Lake breaking the previous (2007) record by 20 cm. This is a lot of water. In 2022, water levels in Southern Lakes peaked some 50 cm lower than in 2021 (see graph below). Nonetheless, this was enough to score 3rd on the post-1970 highest water level record. The most impressive aspect of this event was its date, October 20. This was the latest date on record (by 8 days) for Southern Lakes to peak when Lewes Dam is in its fully open state. The water level was some 70 cm higher than the previous record for that specific date. By contrast, in 2021, we experienced the earliest peak level on July 10. The previous record was July 25.

Summer water levels may return to some form of normal in years to come, but the 2021-2022 sequence will nonetheless remain a clear message about extremes that a changed climate is now able to produce.

Kwänlin (Whitehorse and surroundings):

Considering the record snowpack from winter 2021-2022, Whitehorse residents were relatively fortunate to experience colder-than-average weather in May: a progressive snowmelt helps reduce the risk of property flooding. However, ground saturation caused other problems, such as the landslides on the Robert Service Way, Millennium Trail, and all along the escarpment above downtown and the Marwell industrial area.

Downstream of Kwanlin, Tàa’an Mǟn (Lake Laberge) peaked on July 23rd, 2022, partly as a result of high flows from the Nakhų̄ Chù (Takhini River). These water levels (happening on average once every 15 years; we refer to this as a “15-year return period”), although 50 cm lower than in 2021, caused concern to many Yukoners.

Deisleen Kwáan” (Teslin) watershed:

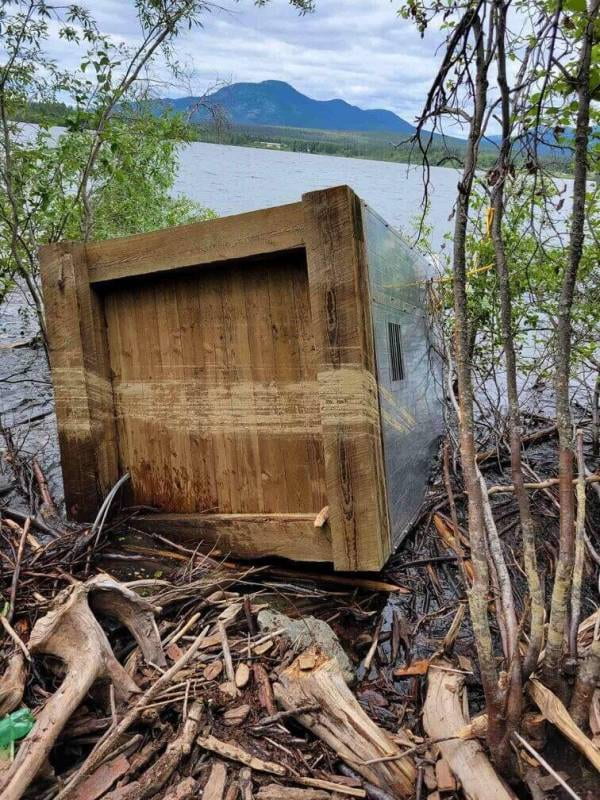

Peak water levels in Deisleen Kwàan are normally controlled by snowmelt. Considering the significant snowpack in the watershed at the end of winter 2022, warm weather early in June and the rain that followed were not welcomed. The peak water level that occurred on June 23 in Deisleen Kwàan was the highest on the Water Survey of Canada (WSC) record since 1962. High water levels and waves caused damage in Teslin, including to the WSC gauge (see picture below provided by Environment and Climate Change Canada). Clearly, improving our resilience to climate change involves designing more robust instrumentation setups in order to monitor its impacts. Current estimates, using the data from 1970 to 2022, indicate that this event had a return period of 70 years. Many people may not even witness an event of this magnitude in their lifetime).

Carmacks area:

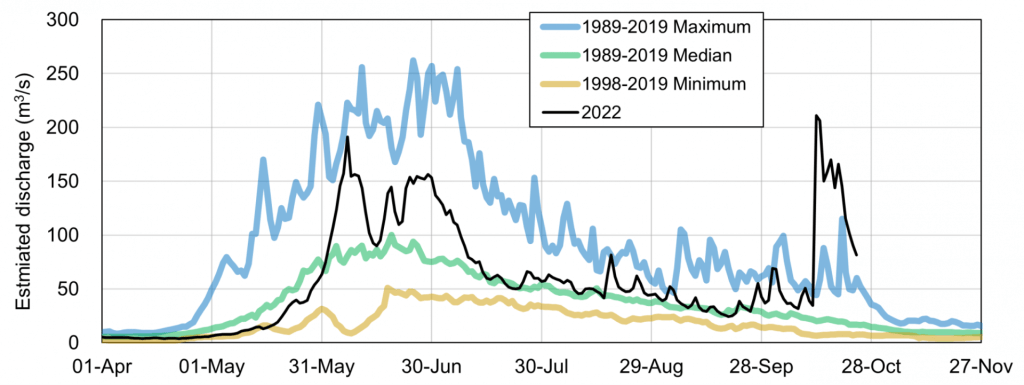

Deisleen Kwáan (Teslin River) is the largest tributary of the Tàgé Cho Gé (Yukon River). Unsurprisingly, flooding in Teslin was not good news for Carmacks. 2021 broke the water level record since 1970, and 2022 broke that by 40 cm (corresponding to a return period of 60 years). Flooding resulted and lasted several weeks. Since then, the community has been working on a flood protection infrastructure (see picture below).

On the Tsâwnjik Chu (Nordenskiold River), current (November) water levels influenced by massive ice production, are already higher than late-May peak levels at several locations, which is common for this type of river.

Ts’ekínyäk Chú (Pelly River), Tu Lidlini (Pelly River at Ross River), and Nä`chòo ndek (Stewart River) watersheds

Central Yukon also received a significant amount of snow during the winter of 2021-2022 and there was little margin, in terms of spring weather scenarios, to avoid flooding. Surprisingly, water levels in the Nä`chòo ndek remained fairly close to their summer average while only minor issues were reported at Tu Lidlini (minor flooding and pedestrian bridge closure for a water level corresponding to a return period of less than 10 years). This latter event was not as dramatic as in 2013 for the community.

ʼAt’aayaat Chù’ (Southern Tutchone) or Tadzan ndek (Hän) (White River):

ʼAt’aayaat Chù’, or Tadzan ndek, behaved somewhat normal in 2022. However, for a third year in a row, this time in June (on the 7), a daily high flow record was established by a very brief and intense hydrological event. The exact cause of this phenomenon remains unknown and should be further investigated – perhaps it was a very intense precipitation event, or a landslide that dammed the flow and followed by its release.

Dawson area

After a unique breakup event in the Tágà Shäw (Yukon River) at Dawson between May 7 and May 9 (link), snowmelt runoff from all parts of the Territory produced a peak flow above 10 000 m3/s (compared with approximately 600 m3/s in Kwänlin (Miles Canyon)). The water level reached the elevation of 318.0 m above sea level, corresponding to a 30-year return period event for open water conditions. However, taking ice jam water levels into account, especially the flood of 1979 (elevation of 320.6 m), high summer water levels in 2022 only represented a 10 to 15-year return period event and the dike was by no mean threatened.

The Tr’ondëk (Klondike River) did not generate a major flood during spring snowmelt. In turn, because of consistently wet conditions, it produced impressively high flows during the entire summer and fall, and broke daily flow records for about 40 days prior to freeze-up, in line with the expected hydrological impact of climate change. The rain also caused several, simultaneous landslides on the Klondike Highway in the Tr’ondëk valley, cutting access to Dawson during several days in late September.

Tth’oh zraii njik (Gwich’in) or Ttth’oh zray (Hän) (Blackstone River) area and further north

Along the Dempster Highway, high flow conditions, caused by late season rain events, prevailed during the entire fall, also setting new daily records at several WSC stations. This condition should also generate unique freeze-up and icing conditions in the next few weeks and months, respectively.

Aalseix̱’ (Tlingit) or Àłsêxh (Southern Tutchone) (Alsek River):

The discharge of the Aalseix̱’, or Àłsêxh, was well above historical average for the entire year, occasionally setting new daily records, but not breaking any annual peak record. This long-lasting hydrological anomaly is not only due to higher-than-normal precipitation, but also due to glacier contribution, including the Tänshı̨̄ (Kaskawulsh Glacier, Southern Tutchone) that used to feed Łù’àn Män (Kluane Lake) through the A’ay Chù (Slims River).

Interestingly, the annual peak flow on the Shäwshe Chù (Tatshenshini River) occurred in mid-October, just like in Southern Lakes (see Figure below), due to a significant rain event (an atmospheric river). Not only did it set, by far, a new daily record, but this runoff event also competed with record high snowmelt (spring and summer) driven flows from previous years.

Liard River

High flows were also expected during the summer in the Liard River watershed because of the significant snowpack. Fortunately, no major rain event occurred in the spring, and the discharge stabilized below 3000 m3/s (a 20-year return period event). Even though this was the 2nd highest water level since 1970, it never got close to the 2012 record: 4000 m3/s, an event associated with a return period of 120 years.

Ch’oodeenjìk (Porcupine River) Watershed:

After a breakup event that involved ice jamming against the Sriinjìk (Bluefish River) aufeis (thick ice made by the freezing of episodic overflow) (link), just like during the significant ice jam flood of 1991, hydrological conditions in the Ch’oodeenjìk went on the dry side of the spectrum in July and August.

Beaver dam release events:

Two major beaver dam-release events made the news in Yukon just a few days apart. A small lake located in the Horse Creek watershed near Män Tlāt (Shallow Bay) almost washed out the Klondike Highway a few kilometers north of Whitehorse. What saved the road was the limited amount of water that was originally contained by the beaver dam. The picture below presents the new Horse Creek aspect upstream of the Klondike Highway, a result of massive fine sediment deposition.

The most significant event happened a few days earlier at Km 900 of the Alaska Highway, east of Watson Lake. The washout caused Internet disruption and interrupted traffic from and into the Territory for several days. The vulnerability of our supply chain became evident once again as many Yukoners noticed when visiting grocery stores.

Kátło’dehé (Hay River), NWT:

A major ice jam affected the town of Hay River, Northwest Territories, in May 2022. It was partially caused by a significant rain-on-snow event that took place before the ice cover had significantly degraded at the outlet of the river. Significant damage was reported.

Extensive research on river ice jams led by professors Larry Gerard, Faye Hick, and Yuntong She, from University of Alberta, has taken place in Hay River over 30 years. Since then, the community has moved away from the Kátło’dehé delta, but apparently, the risk of ice jam flood is still unacceptably high.

It has been several years since a large ice jam affected a community in Yukon. Considering what happened in the neighbouring territory, it is only a matter of time before it strikes again on our side.

Perspective:

The number of new hydrological records set in 2022 in various watersheds of Yukon is staggering. Poorly engineered beaver dams, landslides, and floods represent geohazards affecting life in the North, from the safety of travelers and residents to property and infrastructure damage. This is apparently what a La Niña scenario on climate change steroids can generate. The Climate Change Research group at the YukonU Research Centre is leading studies on both sides of this hydrological story, from documenting current conditions and foreseeing future changes, to proposing adaptation measures that can help improve our resilience to future extremes.

Considering the relatively high late-fall discharges in several Yukon streams and rivers, it would not be surprising to see unusual ice formation patterns in the next few weeks.